INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

A history of violence resonates in Imran Qureshi’s massive rooftop painting at the Metropolitan Museum, and in other shows by Benny Andrews, Nancy Spero, and more.

After the last two massive, vertiginous installations on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which demanded able bodies and rubber soles, this summer there’s a finally a piece everyone can walk on.

But this one is scarier.

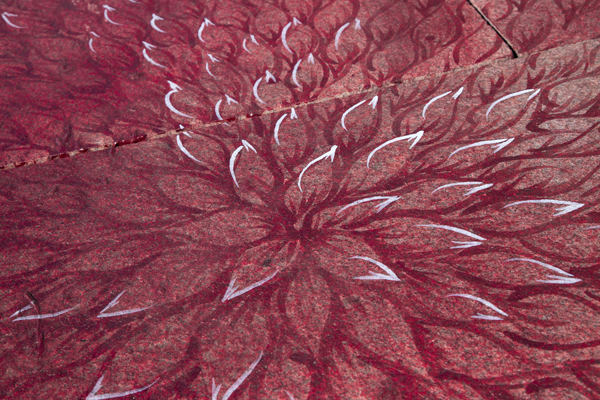

Imran Qureshi, And How Many Rains Must Fall before the Stains Are Washed Clean, installation view, detail, 2013, acrylic. COMMISSIONED BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK FOR THE IRIS AND B. GERALD CANTOR ROOF GARDEN.

photo artnews.com

It’s a landscape painted in situ by Imran Qureshi, the latest artist to make work for the nearly 8,000-square-foot open-air space, and the first commission by Sheena Wagstaff, the museum’s newish chief curator of modern and contemporary art.

Qureshi, who is from Hyderabad, Pakistan, is the first artist to paint directly on the rooftop. Playing off the privileged setting above Central Park, he has rendered bursts of ornamental foliage, exuberant and elegant. They look like enormous details of the gardens in Mughal miniatures, an intricate genre he spent years mastering.

Imran Qureshi creating his site-specific work for The Roof Garden Commission project on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden. PHOTOGRAPH: THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART/HYLA SKOPITZ.

photo artnews.com

In this garden, though, something terrible has happened.

Switching from the elaborate detail of the Islamic miniature to the ritual dance of modernist action painting, Qureshi has splattered the roof in paint, blood-red like the leaves. It takes a moment to perceive the scope of the tragedy that may have unfolded in such a setting. The piece, the artist says, is a response to violence that has occurred around the world in recent decades. He calls it And How Many Rains Must Fall before the Stains Are Washed Clean.

Imran Qureshi, And How Many Rains Must Fall before the Stains Are Washed Clean, installation view, 2013, acrylic. COMMISSIONED BY THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NEW YORK FOR THE IRIS AND B. GERALD CANTOR ROOF GARDEN.

photo artnews.com

There is no shortage of war art at the Met, of course. But at a time when the museum has one Civil War show on view and another opening this month, there is a particular sense of trauma and despair in some of its galleries, especially because so many of the 19th-century images echo what we see in the daily news.

It was as a response to bombings in Lahore that Qureshi began using red acrylic paint in his art, creating tragic landscapes that negate the idea of paradise on earth. While the Met piece was in the works, the Boston bombings occurred. So according to curator Ian Alteveer, the artist “pushed the work a little further,” creating a series more oblique lines, off kilter from the grid. In another symbolic gesture, he decided not to paint the entire surface.

Imran Qureshi, Blessings upon the Land of my Love, detail of a diptych, 2011, gouache and gilt on Wasli paper. PHOTO: COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CORVI-MORA, LONDON.

photo artnews.com

Downtown, near the Holland Tunnel, there’s a violent scene as well, but in this case the victims are just tomatoes, crushed for the juice that Los Carpinteros flung on Sean Kelly’s wall. The piece recapitulates a famous tomato-throwing festival in Spain, where the Cuban-born artists live, but it also evokes the tomatoes thrown in political protests worldwide. These tomatoes would hurt lots more than the real ones, though, because they’re porcelain.

Los Carpinteros, Tomates, 2013, tomatoes, porcelain, watercolor. PHOTOGRAPHY: JASON WYCHE, NEW YORK. ©LOS CARPINTEROS. COURTESY: SEAN KELLY, NEW YORK.

photo artnews.com

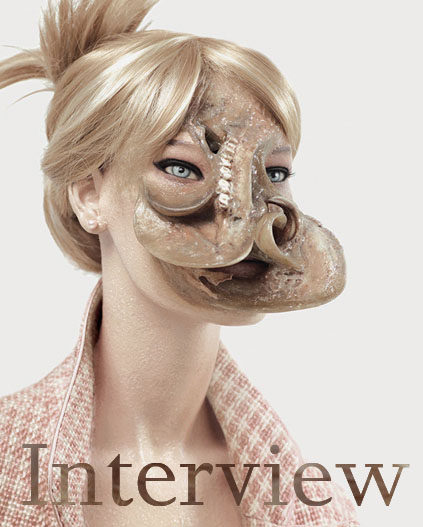

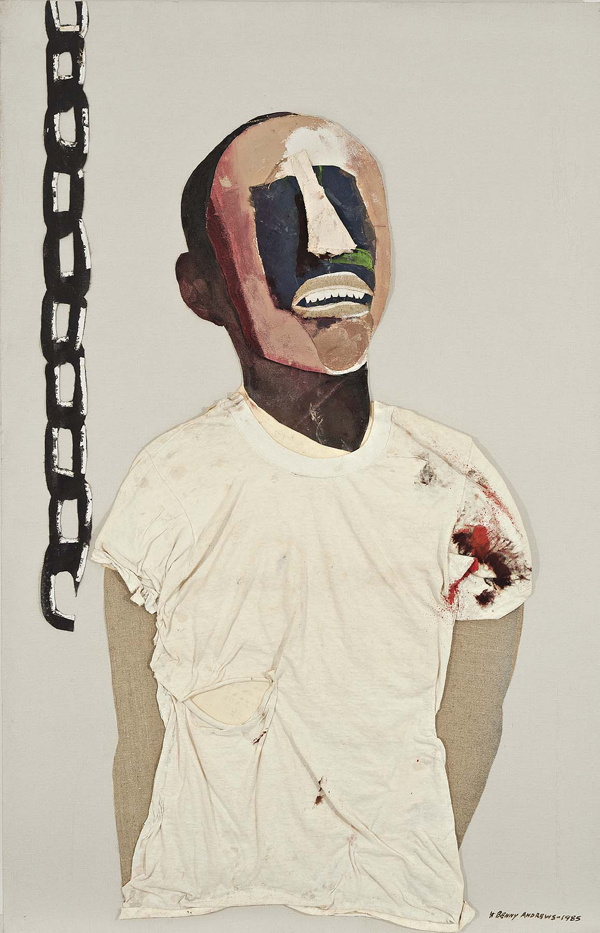

Using the arsenal of paint, painted fabric, and paper collage, Benny Andrews depicts a victim of Apartheid in Study for Portrait of Oppression (Homage to Black South Africans), a 1985 assemblage in the survey of his work ending Saturday at Michael Rosenfeld.

The figure’s nose is flat, his eyes are missing, his hands are pinioned behind his back; the blood splatter on his (real) shirt implies he was tortured. His shirt is torn, Lowery Sims notes in the catalogue, exactly where painters throughout Western art history have rendered Christ’s wound from the soldier’s lance.

Benny Andrews, Study for Portrait of Oppression (Homage to Black South Africans), 1985, oil on canvas with painted fabric and paper collage. COURTESY OF MICHAEL ROSENFELD GALLERY LLC, NEW YORK, NY.

photo artnews.com

Hayv Kahraman, who was born in Iraq, grew up in Sweden, and now lives in Oakland, is featured in the Jameel Prize exhibition, an initiative of the V&A that spotlights artists whose work responds to Islamic tradition. The show arrives at the San Antonio Museum, its last stop, on May 24. Here, too the victim’s eyes have been erased, as the woman on the noose is forced to hang herself.

A cry of pain is arising from the Worcester Art Museum, where Nancy Spero’s stunning, devastating, Cri du Couer (2005) goes on view this Saturday. The work, the artist’s first after the death of her husband, Leon Golub, echoes a procession of female mourners, like those in the tomb of Ramos of Thebes. With its mix of vigorous, hand-painted color and silk-screened images, the piece suggests not only the artist’s own bereavement, but, as Roberta Smith put it when the work was first shown, at Galerie Lelong, “a world declining into violence, chaos and bottomless grief.”

Nancy Spero, Cri du Coeur, detail, 2005, hand-printing on paper mounted on polyester poplin. ©ESTATE OF NANCY SPERO/LICENSED BY VAGA, NEW YORK, NY. COURTESY GALERIE LELONG, NEW YORK.

photo artnews.com

Like Qureshi’s work at the Met, Spero’s tour de force echoes a famous comment Harold Rosenberg made (in our pages) in another context: “It’s not just a picture, but an event.”

Qureshi stresses that his work is not just a lament over violence but an expression of his hope for regeneration.

Already, little green buds—real ones–are peeking from the cracks in the tiles. How long before they get crushed?

via artnews.com