INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

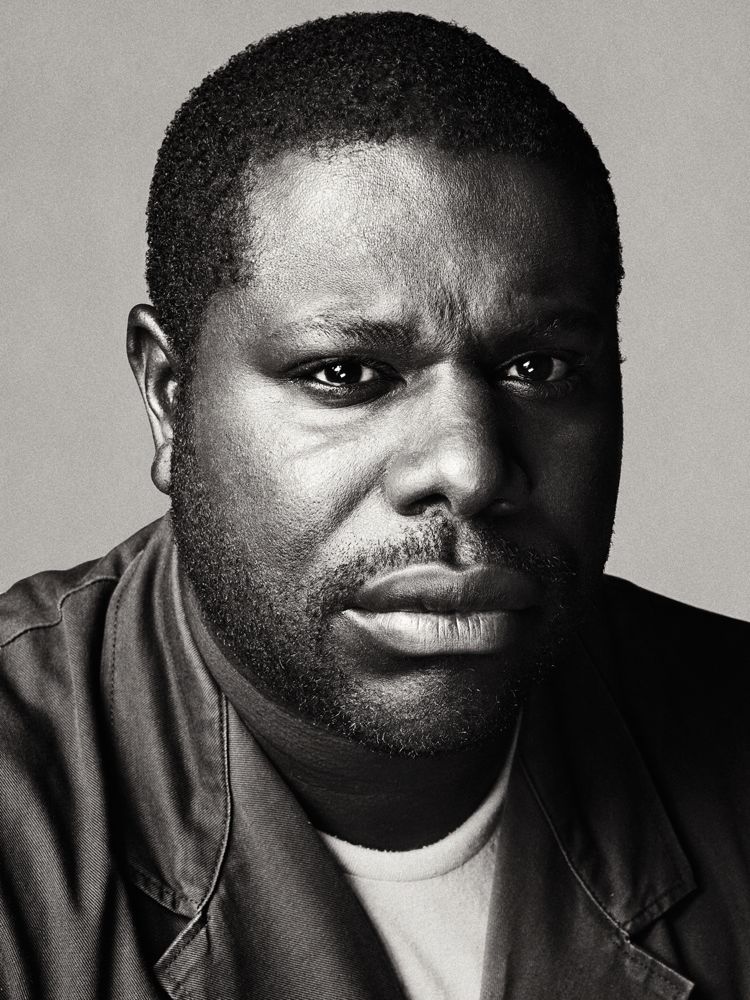

If he were at all comfortable talking about what he does, Steve McQueen would have plenty to brag about. The 43-year-old British artist-turned-director won the Turner Prize in 1999 and went to Iraq as an official U.K. war artist in 2003. He’s represented his country at the Venice Biennale, been granted the title of Commander of the British Empire, and his work is in museum collections all over the world. In 2008, when McQueen started directing for the big screen with Hunger, and then with 2011’s Shame, he gathered up fawning critics and film-festival awards in the palm of his meaty hand. Still, despite endless wins and nominations, despite having just signed Brad Pitt to his next film, despite two new solo exhibitions (at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Schaulager, in Basel, Switzerland), McQueen is not exactly luxuriating in his moment. “I’m never satisfied with what I do,” he says. “And I hope that shows up in my work.”

It does. McQueen’s films, photographs, and sculptures are challenging—in his video “Caribs’ Leap,” the men falling through the sky allude to the mass suicides in 17th-century Grenada, and his installation Queen and Country, of postage-stamp portraits memorializing Britain’s Iraq-war fatalities, toured the U.K. and drove home the war’s devastation.

His two feature films, Hunger and Shame, both explore situations of captivity through brutally carnal performances and uncomfortable camerawork. In Hunger, about the IRA hunger strike protests, Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) and his fellow prisoners have nothing left to protest with but their own bodies. “Sands transcended prison by not eating,” McQueen explains. “And Brandon [Fassbender’s sex-addicted character in Shame] puts himself into a kind of prison by engaging in repeated sexual acts.” They’re raw films, but there is a dignity given to the characters that makes one believe McQueen when he says, “I like people”—despite how much he tortures them onscreen.

The director Steve McQueen has found a way to constantly include the element of surprise in his work, both as an artist and as a filmmaker. It would be dismissive and reductive to say that he operates on pure instinct, but what he has done with his installations—such as his video pieces Bear (1993) and Five Easy Pieces (1995)—comments on the way that we inhabit space, and how subtly and insidiously shocking it is when our intimate spaces have been violated. He often seems surprised himself when he’s asked about the unrelenting power in his work. The three feature films he’s responsible for as director—Hunger (2008), Shame (2011), and his latest, an adaptation of Solomon Northup’s 1853 narrative Twelve Years a Slave, which is out this month—all explore the notion of having someone’s personal space invaded, and how the protagonists in each film deal with that issue.

Given how unflinching his productions have been, the 44-year-old McQueen is remarkably gentle and thoughtful—so much so that he will request a moment to consider a question, and turn it around in his head to get the shape and weight of it, before answering, occasionally with an excited rush of words in response. (And I’m hard-pressed to remember a conversation with him, be it an interview or a chat over tea, that hasn’t included a chuckling, “I hope that won’t stir up too much trouble …”) That has been my experience with him since we became acquainted a few years back, after the American release of Hunger. He has an insatiable desire to understand and to be understood; if his work stimulates conversation—demands it, really—then so much the better.

-read an interview via theinterviewmagazine.com and wmagazine.com

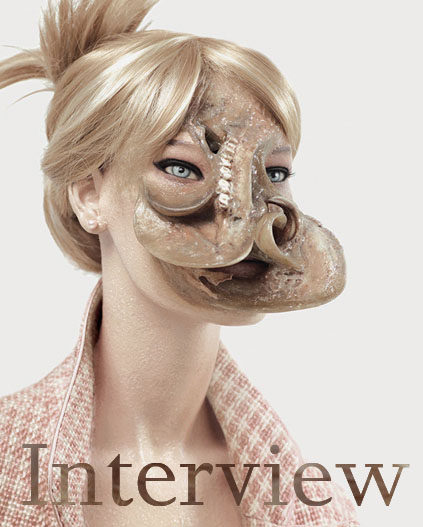

Photography SEBASTIAN KIM

Stylist MIGUEL ENAMORADO

STEVE McQUEEN IN NEW YORK, AUGUST 2013. ALL CLOTHING: McQUEEN’S OWN.

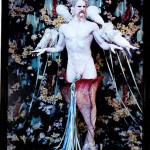

STILL FROM 12 YEARS A SLAVE. CHIWETEL EJIOFOR (MIDDLE LEFT) AND QUIVENZHANÉ WALLIS (MIDDLE RIGHT). PHOTO: JAAP BUITENDIJK; CHIWETEL EJIOFOR AND MICHAEL FASSBENDER. PHOTO: FRANCIOS DUHAMEL