INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

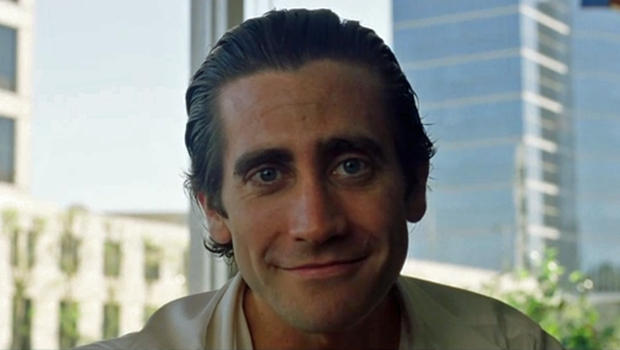

One of the biggest disappointments this Oscar season was the paltry single nomination for what has been a standout thriller this year. The name is Nightcrawler and the game is entrepreneurship. Jake Gylenhaal gives one of his best performances yet, and should have seriously been considered for best actor, if not the whole film for best motion picture.

The film begins with a simple character proposition. A young man is looking to fulfill his American Dream in any way possible. He sells spare (stolen) metal and tries to put himself in a position to get a job. With the low expectations you would expect from a post-recession twenty something, he experiences the similarly expected straight refusal of the established middle aged, defending their trade in front of their younger counterparts. The economic undertone of the film is here set, only to be abandoned as a forward looking element of narrative. The story follows Louis Bloom as he persistently negotiates his way into a high-earning career. Unglamorous but alert, he quickly becomes a night-time cameraman for morning news shows. He is there to photograph the unseen horrors which threaten the serenity of the morning viewer, the hidden dangers waiting to spill into the day.

Nightcrawler essentially looks at the darker side of desire, the shadows of the personal pyramid and what twisted conclusions models of management can bring. To be clear, I see no difference between Nightcrawler and Wolf of Wall Street. The difference between Scorsese and Dan Gilroy is the choice of metaphor and depth. One uses the conventions of the mobster film to portray the criminality present in the financial system, while the other sinks deeper into the damaged psyche of profit-making. With his repetition of TedX mantras of leadership, Louis Bloom often feels like the personification of an internal memo from JP Morgan. The lengths of his rhetoric and the way he cannot abandon this language highlight his traits as a psychopath and are the only genuinely creepy things he does(bar killing people that is). Furthermore, the choice of hair do, words, cars create a distance between him and the emotionally invested world around him. The only clue the movie gives about this is his desire to create a working business from his camerawork.

Moving through the narrative, the way Nightcrawler conjures all social relationships is perfectly transparent towards models of economic domination. The business partnership, here shown as the attempted fraternity between two fellow night cameramen, ends in a classic tale of sabotage. The zero sum game has only one winner, and Gylenhaal’s eerily calm character understands this better than Bill Paxton’s character, Joe Loder. His only employee, Ricky, works as a clear reference to the exploitation of young workers for internships in what are ‘career altering’ perspectives, and ‘unique opportunities towards self-advancement’. He will meet his end on tape, recorded by his self-affirmed benevolent employer. Finally, Bloom’s relationship with his boss, the morning news program director is a variation of metaphors on power, from money, to sex, and finally violence.

Jake Gylenhaal’s character merely wants to make more money, and he applies himself in a persuasive way towards this goal. This hollowness of spirit, with the human only in charge of his margin projection, is the founding element of his criminality and lack of empathy. His business model never includes sentimentality and is what makes him a killer. This cinematic monster is unique due to this capitalist inclination and might very well spark a new genre of economic thrillers. Given Nightcrawler’s fairly good run at the box office, I see no reason why it shouldn’t.

by Paul Dunca

Paul Dunca is a freelance saboteur looking for a change of pace. He writes reviews and opinion pieces to keep appearances and can be reached at various wishing wells around London.