INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

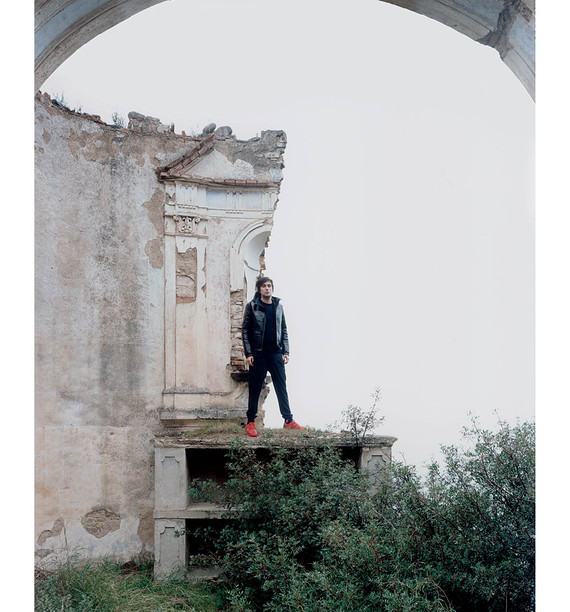

FRANCESCO VEZZOLI is standing in the nave of a dilapidated, roofless 19th-century church in Montegiordano, a tiny town on the sole of the boot that forms southern Italy. He wrinkles his nose as he surveys the scene. It’s raining—an uncharacteristically gloomy day interrupting this part of the world’s sunny spring—which is hindering a video shoot he’s producing. “I guess God is not so into artists who destroy churches,” he says, a boyish grin suddenly lighting up his face.

Vezzoli, 42, bought this church last year. He first viewed it on the Internet before purchasing it with plans to dismantle the 1,500-square-foot structure, load it onto a boat and ship it to New York, where it will be reconstructed in the courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art’s PS1 exhibition space in Queens. It will house a series of his glitzy, celebrity-packed video artworks as one phase of the artist’s international retrospective, which he has christened “The Trinity.”

This church constitutes one of the three tentpoles of Vezzoli’s oeuvre, which he identifies as “art, religion and glamour.” For his retrospective, he conceived of three different shows in three different cities. A show at Rome’s MAXXI (the National Museum of 21st Century Arts), which opened in May, addressed the first because, as Vezzoli states, “it’s the most important museum for my nation.” The second tenet is reflected in the installation of this church at PS1, titled The Church of Vezzoli. “Art is definitely a religion,” says Vezzoli. “You can’t deny that people who believe in art believe in something you can’t see.” And finally, a star-studded show early next year at Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art. “Last stop: glamour! That’s the deadly one.”

He’s well versed in its allure, having experienced its power firsthand. The piece that put him on the map was a glitzy 2005 video starring Helen Mirren, Courtney Love, Milla Jovovich and Benicio Del Toro in a trailer for a nonexistent remake of Gore Vidal’s erotic film Caligula, complete with togas designed by Donatella Versace. (The video features Vezzoli as the incestuous emperor.) Though only five minutes long, its combination of lurid celebrity and political satire immediately caused a sensation for when it first screened at the 2005 Venice Biennale. Such themes have been constant for Vezzoli, whose list of leading ladies includes Nicki Minaj, Veruschka, Sharon Stone and Catherine Deneuve. In 2009, he staged a work ambitiously titled Ballets Russes Italian Style (The Shortest Musical You Will Never See Again) at L.A.’s MOCA, a performance wherein Lady Gaga, wearing a crystal chandelier dress codesigned with Miuccia Prada and a hat specially created by Frank Gehry, belted a song from a rotating Damien Hirst –designed hot-pink piano while ballet dancers from Moscow’s Bolshoi danced around her. “His point of view is never banal,” deadpans Vezzoli’s dealer Larry Gagosian.

Fame as faith is a dominant thread throughout his work. “Hollywood is a religion too,” he says, speaking of The Church of Vezzoli, which will screen such videos as 2009′s Greed, an ad for a nonexistent perfume directed by Roman Polanski, featuring a catfight between Michelle Williams and Natalie Portman. “This is a project about my work. It describes my fascinations, my obsessions and, of course, the makeup of how glamour relates to the dynamic of religion. If you look at the saints and you compare them to the life of pop stars, you see it’s all about creation of fascination, the creation of myth.”

Vezzoli cannot remember the first time he met Prada, but refers to her in conversation as his “best friend.” They travel together to fashion events, art fairs and wellness spas. Prada also doesn’t remember how they became friends, but she was an early convert to his artistic fold. “Before I met Francesco in person, I got to know his work: It was a 2001 performance with Veruschka at Harald Szeemann’s Venice Biennale,” she remembers. “It was a perfect manifesto for the art he was doing in those first years: the glamour of the past, the pain, the voracity of the contemporary world that wants to appropriate and to fetishize the story of a diva, of a myth.”

In person, Vezzoli is charming. He wrings his hands together when he’s nervous, his brown locks fall into expressive brown eyes and he’s never at a loss for a compliment at an opportune moment. “He’s a master of seduction, that’s part of what he does,” says Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA’s PS1. “He’s incredibly modest, or so it looks. And, at the same time, incredibly demanding. There’s a strategy of the eternal boy who needs to be happy.”

Vezzoli was born in Brescia, a small Italian city at the foothills of the Alps. He was a precocious only child who entertained his parents—Luciano, a lawyer, and Titti, a pediatrician—with his wild imagination. Titti once told an art critic that her son became an artist so that he could do all the things he wanted to do when he was 5 years old. For his part, Vezzoli jokes that he moved to London “to go clubbing” and enrolled in Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design so he wouldn’t have to leave England, graduating in 1995. That put him in the British capital just as the local art scene was bursting with provocative, exciting and newly rich artists, like Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Jake and Dinos Chapman.

Nearly 10 years younger than many of the so-called Young British Artists, Vezzoli wasn’t yet part of the “in” crowd. “It shaped me in the sense that, from the outside, I basically saw the birth of the last artistic movement that was completely shameless with the media. It inspired me to be more analytical about [the art world],” he says. “I felt completely overwhelmed by a universe that I couldn’t overcome or live with on an egalitarian level. London was so strong and blossoming. Young British art was exploding. When you went out, you would see John Galliano and Kate [Moss] on the dance floor. I was just this Italian kid from the suburbs. So I went back to Italy and squeezed my brain and thought, What do I have to say?”

He retreated to Brescia and focused on his work. The results have been criticized for relying too overtly on references to modern pop culture—for being “too cheesy,” as Vezzoli says. Yet he cannot be accused of being uninformed. “He is able to mix pop culture references with erudite literary ones. I find this investigation into issues of celebrity and fame intriguing,” says Gagosian. He is as comfortable referencing Us Weekly as ancient texts. And Vezzoli is as loyal a fan of old Hollywood studio films as the tacky Italian reality TV shows he watches until the wee hours in the Milan apartment he keeps in a friend’s office building. (He also owns an apartment in Milan’s Casa Galimberti building, infamous because of its history as a brothel and the paintings of women in various forms of undress on its exterior. But he has never moved in because he says he’d rather spend time creating art than redecorating a home.) He travels often, but when in Milan, he can be found most Saturday nights at the nightclub Plastic dancing until dawn, although he is a strict teetotaler.

His Sunday schedule, however, does not usually include mass. Vezzoli was raised Catholic, but he no longer practices, which helps him detach from the spiritual hang-ups of razing a sacred building. “I’m always ambiguous in my [spiritual] state, so in my mind I’m going there to destroy it and save it at the same time,” he explains. “I’m tearing it down, but then I’m rebuilding it in a safer place.” Indeed, after looking at several churches around Italy, it was the precarious position of this one, perched on the edge of a cliff, that hooked Vezzoli.

via online.wsj.com