INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

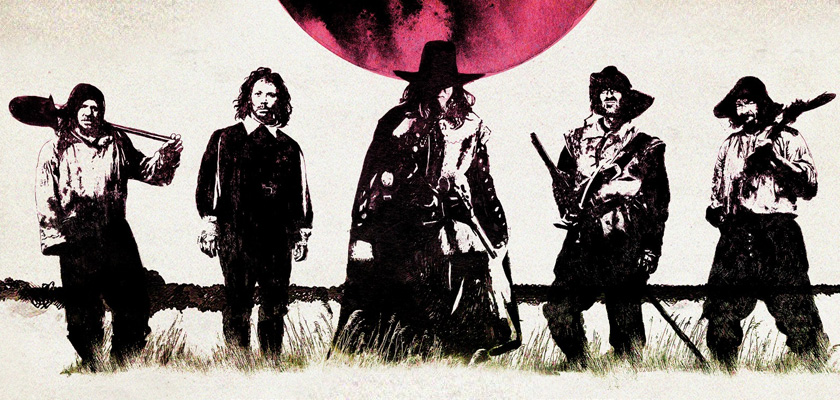

Discussing such a truly engrossing and complex film like Ben Wheatley’s 17th century English Civil War supernatural drama, A field in England, is a difficult task. That statement alone only offers slight indications of the cinematic feast that the British director prepared with his latest instalment. With layers of symbolism and powerful aesthetics wrapped around a story dealing with the occult and the mystical, the movie captivates through its resilience to conventional interpretations of cinema.Torn by conflict, the space inhabited by the characters is restricted to war and religion.This makes any reading of the film rely on power relations and allegory.

The plot follows four deserters who meet on the battlefield and decide to leave together in order to escape capture. Whitehead is a noble’s servant in search of a former disciple of his master that stole alchemy books, later shown as O’Neil. He is the main character of the story, and the plot mainly revolves around his development. A pious man with fear of God, he transforms by acquiring self-consciousness, as he abandons the rigours of his teachings to battle O’Neil’s evil ways. Complementing him is Trower, a thief whose rotten character extends to his physical health(‘Am I turning into a frog?’’Tis the one complaint you do not suffer from.’).

Trower drinks and swears and formally repeats that he is his own man, setting up the main theme of Whitehead’s development but also ironically pointing to his capture by O’Neil and his servant. Another supporting role is Friend (Trower ‘names’ him as such), a cheerful Essex peasant who sees life as an obstacle course between divine punishments. Hejokes, smiles and is fascinated with hands and handcrafted tools, pointing to a purity of the simple man that takes life as it is. He is also the only one to break the violence-religion barrier, with a song that correlates both to Trower’s salvation and to Whitehead’s awakening. Lastly there isO’Neill, who is revealed to be Cutler’s master and the reason the latter suggested to the other three to go towards the alehouse, who is an alchemist seeking treasures to pay off debts. He wishes to use Whitehead’s conjuration powers to find these and is aware of the main character’s real strength.

The four men initially head towards an alehouse as a marching band without a leader. Their first collective action is pulling a rope that leads them to O’Neil, when their purpose is revealed(the henchman, the treasure-seeker and the two workers). At this point, Whitehead is only a coward, unaware of the world or his self, as O’Neil points out. He enslaves Whitehead and forces him to look for a treasure site, also making him break his fast and drink wine.

As Neil’s plan progresses and Trower and Friend dig deeper for the treasure, Whitehead becomes more inward looking. His vision of a foreign planet crushing the earth bears a resemblance to an iris, the world looking into the character. This, along with the runes with unknown writings that he coughs out, isone of the visual metaphors that point to Whitehead’s inability to know himself and his true power. Finally, Friend’s song triggers his catharsis, as he embraces the evil that O’Neil represents in order to foil his plan. Blindly ingesting mushrooms as he is chased around the field, a visual play on identity between the two opposing characters occurs. Finally, the revelation of the digging spot as a burial ground that holds mystical powers confirms Whitehead’s transformation and true form, of a charlatan and a killer with great power.

The visual style stands out through the choice of black and white instead of colour. The bleakness of the imagine favours a strong use of sound in telling the story, with hard-hitting, psychedelic drums and repetitive guitar samples(think Wender’sKings of the Road or Refn’sValhalla Rising) that punctuate and enforce the narrative. Walking through plains and meadows, the audience never sees any structure or sign of civilization, creating a sense that the characters journey through a stateless land. The role of mise-en-scene is further enhanced by tableaux that the characters create at the beginning of each ‘chapter’ through stand-still poses.

As the story reaches its climax, with the 10 minute hallucination scene that the main character experiences, the sense of paranoia and loss of control is enforced by stroboscopic sequences, kaleidoscope effects and higher frame rate. These film-making elements are normative rather descriptive, as the experience of the characters trickles into the visual style of the film.

Ben Whitley covers the film with numerous artifices that capture the attention of the audience, creating a unique sensory experience outside of classic formulas and worthy of the alchemy theme of the film. In the end, A field in England is a single-standing tale of emancipation and unleashing of human potential, as the protagonist takes on the role of the coward, the faithful, the slave and finally the master. ‘I shall pray for more legs and hands to better appreciate the wonders that play out beneath us.’ Whitehead’s ultimate desire to know and feel more reveals a very humane message in A field in England, perhaps fitting for an English Civil War film.

Paul Dunca is a freelance saboteur looking for a change of pace. He writes reviews and opinion pieces to keep appearances and can be reached at various wishing wells around London.