INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

The Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum’s recent acquisition of an iPad app code was accompanied by a lengthy rationale on its blog: “[S]hould the nation’s design museum not begin to acquire the underlying source code of all its objects?” it asked, somewhat defensively. Surprising as this immaterial design acquisition may have been to some, it comes on the heels of what have been a slew of similar tech-oriented exhibitions blurring the distinction between science center and arts and design museums. The C++-written code for an iPad app actually represents a confluence of their recurring themes, not the least of which is navel-gazing about the influence of technology in our lives. “Is the future really here?” these exhibitions obsessively ask us. (A recent London Design Museum exhibition answers, “yes.”)

ARTINFO targeted five new high-tech tropes now in heavy rotation throughout various institutions of art and design, particularly in London and in New York, which forecast the future of exhibition, sometimes presenting themselves as passing fads, a little too excited about and self-aware of their novelty. The iPad app code itself checks three out of five boxes, despite the fact that we’ve intentionally left the acquisition of other Apple-related items items off of this list (truly, that’s so 2011).

3-D Printing

Kudos to Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum’s acquisition of the world’s first 3-D printed chair, Patrick Jouin’s 2C — it treats the technology as another regular form of manufacturing. But elsewhere, 3-D printing’s sycophantic fanfare is reaching its saturation point; the once-enigmatic technological marvel is starting to lose its mystery via general ubiquity, and yet museums continue to treat it as an impressive novelty. This year alone saw the Makerbot churning away inside the Museum of Arts and Design during a spring “After the Museum” exhibition; an exhibition at the London Design Museum claiming that the technology heralds “A New Industrial Revolution” (a claim, to be fair, we also made — in 2011) ; a global survey of 3-D printer design files at the New Museum’s “Adhocracy” in March; and the January opening of The DRC Industrial Design and Creative Industry Base, a Beijing museum that allows visitors to 3-D print copies of… anything they want. And there’s more to come: both at the Victoria & Albert Museum’s “Digital Design Weekend” on September 21-22 during the London Design Festival, and, later, the MAD’s “Out of Hand: Materializing the Postdigital” in mid-October. We offer another glimpse into the future: It’s going to get really old, really fast.

There’s an App for That (So You’re Going to Need an iPhone)

Are curators now predisposed to favoring the tech-savvy? The growing number of gallery exhibitions that require a smartphone just for viewing suggest this might be the case. The buildings of the future presented by Storefront for Art and Architecture’s winter “Past Futures, Present, Futures” required a QR code reader; New York design gallery R’Pure’s exhibition of “Architecture in Augmented Reality” in late 2012 required the Urbasee iOS app in order to view the scale models; and more recently the artist Jon Kessler, touting the Internet as an “organism,” wove augmented reality into his spring Swiss Institute installation, “The Web.” Augmented reality is also now used in a decidedly lower-brow design display: Superimposing images from the Bible-sized Ikea catalog in your living room.

Social Media

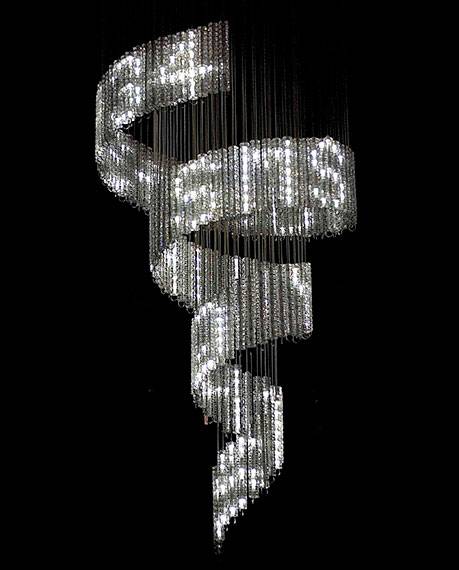

By uploading its newly acquired source code to the online filesharing platform GitHub, the Cooper-Hewitt integrated the use of social media into exhibition; this is a growing trend museums have been using to bait more viewer interaction (read: attention). Examples include the LED Swarovski Lolita chandelier Ron Arad hung from the V&A’s ceiling to scroll comments from the Twittersphere in 2012, and the August “Living Large While Living Small” show in which subjects blogged, Tweeted, and Instagrammed messages while living in the Museum of the City of New York’s micro apartment installation. At the upcoming London Design Festival, see your own Tweets scrawled across artist Man Bartlett’s “Grey Matter” installation at the V&A.

Hacking

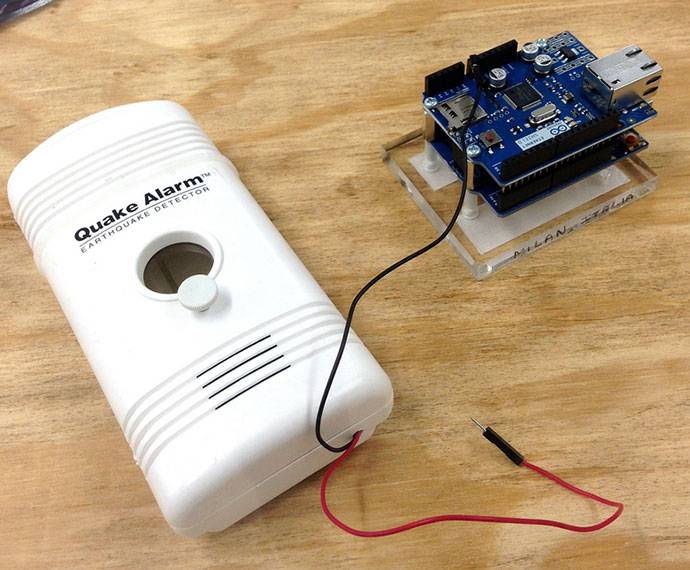

Hacking may be far from newly used as an artistic discipline, but recent design exhibitions posit the form of computer nerdery as a DIY means of appropriating existing forms and rejiggering them towards practical innovation. Cooper-Hewitt’s hope is that viewers who download its newest acquisition will hack new life into it: “[A]nyone can now look at, download, and play with the source code that makes this app. Not only that, you are permitted to replicate, modify, and transport it to other hardware platforms and devices.” In April 2012, the ever-progressive FuoriSalone in Milan devoted the entire basement of a major luxury shopping mall to “Hacked,” an exhibition in which visitors could download open-source designs of buildings, houses, and objects; in the same space one year later, a pair of designers called Dentaku hacked basic cell phones into musical instruments in a show called “Cellular Sounds.” In the spring, the New Museum’s recent “Adhocracy” exhibited the Arduino, an open-source piece of hardware programmable for various design uses from flashing light displays to auto-Tweet machines. Curator Joseph Grima is skeptical of referring to this as “hacking,” not only because the term “has been used so much in so many different contexts as to become somewhat threadbare in terms of meaning,” he told ARTINFO, but because “it somehow implies the violation of an object”; nevertheless, he did agree on it being relevant to his discourse.

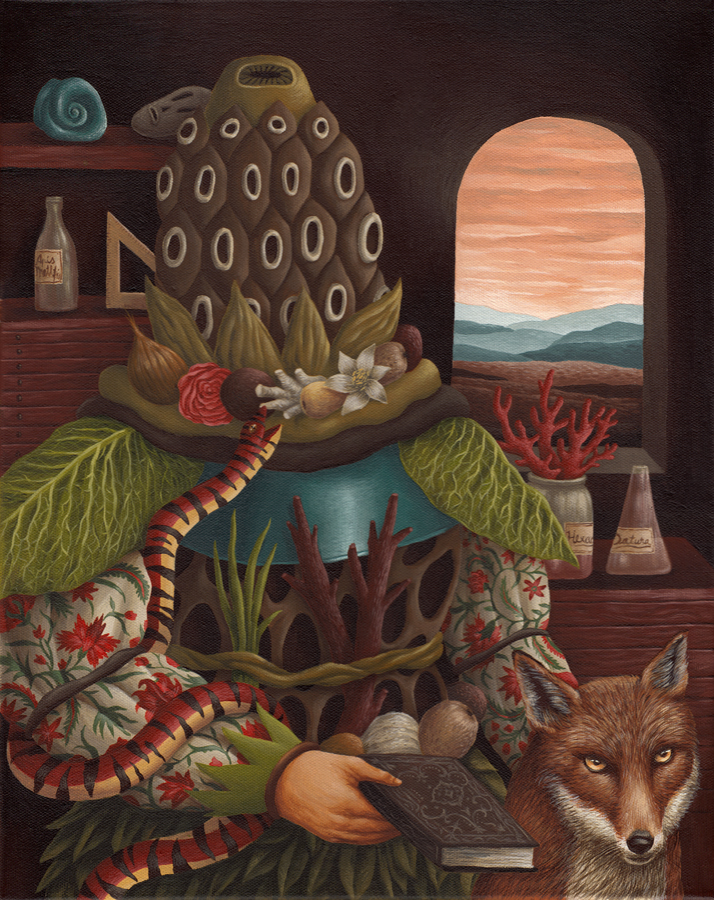

Biomimicry

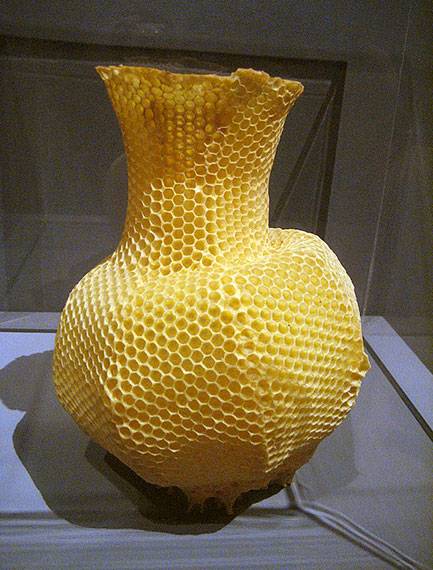

More on the emerging rather than over-saturated side, a trending technique of appropriating nature’s methods of production is gaining prominence: Paola Antonelli’s ongoing “Applied Design” exhibition at MoMA featured Tomáš Gabzdil Libertíny 2006 Honeycomb Vase, which was literally made by bees (you might have missed this is if you were too busy playing Pac-Man). The method plays a more prominent role at the V&A during the London Design Festival, at which London-based think-tank the Institute of Unnecessary Research will present how its findings on microbes could result in antibiotic textiles.

via blouinartinfo.com