INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

Every now and then I come across an artist who embodies that alluring and at the same time riddling antinomy I expect from a creative personality: an educated, (but still) intelligent mind with a pinch of rebelliousness, a candour of the artistic labour and a plurality of the medium in which the work is created.

This is the legacy of Walter de Maria. Though an unfamiliar name for the general public, de Maria decided to be on the map in other ways. I mean literally, on the map.

His most famous work, The Lightning Field (1977) expands over an area of one kilometre long and one mile wide in the desert of Western New Mexico, USA. Four hundred poles made of polished stainless steel with pointed tips are mathematically arranged and fixed into the ground 220 feet apart (this guy really had a sense of humour with choosing numbers!), thus creating a monumental installation which visitors can not merely look at from afar, but also walk through at appropriate times.

The well-directed artistic intention of de Maria takes effect not only during storms – as the poles are murderous conductors of electricity – but also at specific hours of the day. During sunrise and sunset, the visual performance created by the light gradations on the poles are said to be memorable. On one hand, de Maria managed to praise the higher forces of nature while still making it accessible and somewhat playful. On the other hand, his expansive thinking materialized into something that goes beyond the narrow spaces of traditional art quarters such as galleries or museums.

Another attempt to override artistic conventions was the Vertical Earth Kilometre (1977) in Kassel, Germany, included in that year’s Documenta. In this case, the work is ironically hidden from view and placed into a borehole in the ground. One thousand metres of solid bass cut into six metre sections were inserted in that bore, making visible only the top part which quizzically sits level to the ground. If this is a game of hide-and-seek, I honestly think that Walter is the winner.

Additional to the list of viewer-interactive works is The Broken Kilometre (1979) located in New York, USA. Five hundred solid brass rods, of two metres in length and two inches in diameter apiece are placed in five parallel rows of one hundred rods each. The artist’s mathematical precision goes even farther as the distances between the rods increase by five mm with each consecutive space, from front to back. The prodigious work occupies the wooden floor of a monumental hall, illuminated by metal halide lighting fixtures.

This is not the only work by de Maria commissioned and maintained by Dia Art Foundation in New York. An earlier piece, The New York Earth Room (1977) can also be found under the same patronage and is the last remaining of three similar Earth Room sculptures (the first in Munich, Germany – 1968, the second in Darmstadt, Germany, 1974). The title of the work doesn’t convey anything; on the contrary, it overtly denominates the indoor art-piece: a 335-square-metres floor space evenly covered with 197 cubic metres of earth.

Adding-on to the list of works, I should mentions 360° I Ching (1981) and The 2000 Sculpture (1992) which are demonstrations of how art can be too elusive to the viewer’s visual coherence. De Maria manages to conquer difficult spaces by moulding them into Minimal sculptures of massive proportions and meticulous display that trigger a reflective state of mind. “No matter how pure I try to be” the artist noted in 1968, “something always enters in, a streak of non-purity. It’s a point where warm meets cold, action meets inaction, that’s what interests me. And what goes on in people’s minds”.

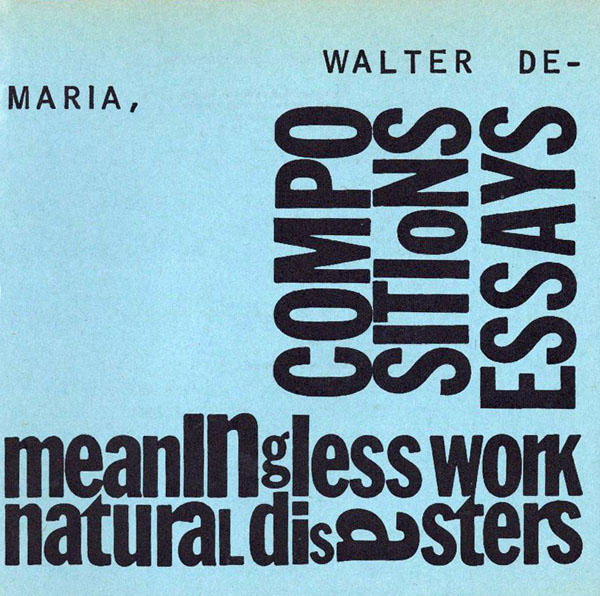

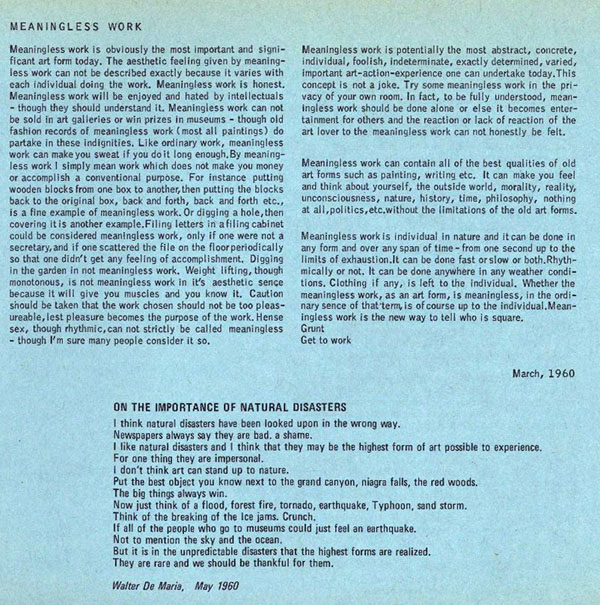

Such artistic convictions of Walter de Maria are harboured in some of his essays that are quick-witted and genuine with taunting titles: On the Importance of Natural Disasters, Art Yard, Beach Crawl, Meaningless Work (I just love it when a great artist is being modest about his art).

Among so many seriously conceived works of art, I will raise the barometer of coolness by pointing out that de Maria was also a talented drummer, playing alongside of Lou Reed and John Caleb in The Primitives (a New York-based band which was a predecessor to The Velvet Underground).

I must admit that it is distressing for me that Walter de Maria’s death earlier this year is an inducement of his work being recollected in various articles (this being included). However, it’s never too late to recognize good art, especially when it is waiting for you in open field.

by Cristiana Șerbănescu

Cristiana Șerbănescu is allergic to describing herself to the public. The one thing she is sure of is that she wants to come to terms with her own artistic differences. She is now attempting to INHALE.