INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

By the time I arrived at James Beckett’s collages depicting naked girls from porn magazines presented alongside images of luxury watches at Galerie Krinzinger, I couldn’t stop the thought coming into my head: women still have a pretty bum deal in the art world. The conclusion was somehow confirmed by a Nan Goldin chromogenic print at Matthew Marks, Eyes (2013), depicting various examples of the female form in art history, so often reduced to an objet d’art for the patriarchal gaze (though Goldin’s eye subverts this, somewhat). Then, I came across Broadway 1602, and a work by Penny Slinger – Bride Book (Wedding Cake – A Bride’s Prayer) (1973), in which collages present the bride as a joyous wedding cake, cut open at various choice points, including the groin. But Slinger’s did not feel like a statement on subjugation by gender. More so, the humour turned the piece into a celebration of woman as a force equal to man, but ultimately different. Perhaps this is the prayer in Bride Book – that woman might be taken as Mistress to the Master.

It was with this thought that I left Frieze London for Frieze Masters, now in its second year and by all accounts, a visual delight. The fair presented an array of work from in and around the canon (or various canons) dating from as far back as antiquity up to the year 2000 by 130 galleries from all over the world. Of course, women were everywhere, too. A bare-bodied Carla Bruni by Annie Leibovitz at Bernheimer; a remarkable Jean-Léon Gérôme gilt-bronze sculpture of a naked woman adorned with jewels perched on a Corinthian pedestal (conceived in 1903) at Daniel Katz, also showing a wonderful terracotta sculpture of a gorilla abducting a gladiator by Emmanuel Frémiet (provenance, 1876).

Featuring 24 solo presentations by galleries curated by Adriano Pedrosa, 11 out of the 24 artists showcased this year were women – a pretty good ratio: almost fifty-fifty.

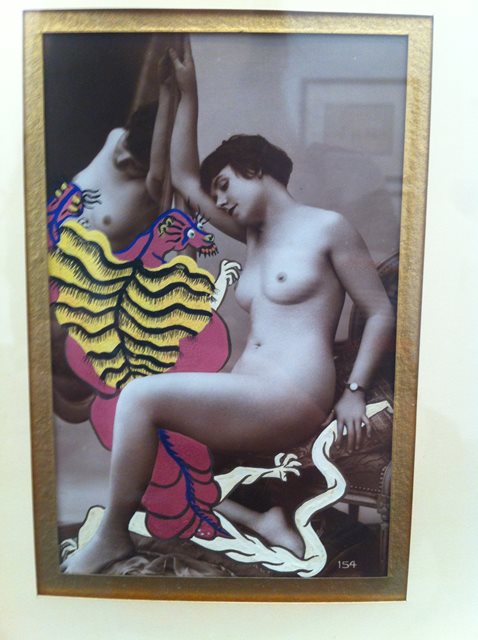

There were examples of William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s sensuous bodies at Didier Aaron & Cie, and an exquisite quartet of gouache interventions onto women’s bodies portrayed in carte postales by Georges Hugnet at Ubu Gallery (with Gallery Berinson), not to mention a fantastic ‘hanging candlestick mermaid girl’ from sixteenth century Germany at Sam Fogg. There were also women artists throughout the fair, too: a few at least, notably Lygia Clark at Dan Galeria, Anna Zemankova at The Gallery of Everything (also showing incredible sculptures by ACM), an ethereal Bolero by Lynda Benglis at Cheim&Read, works by Dorothea Rockburne at Jill Newhouse, Yayoi Kusama at David Zwirner and the ever-wonderful Christina Ramberg at Emmanuel Von Bayer and Corbett vs. Dempsey (with Thomas Dane Gallery). And Cindy Sherman and Jenny Holzer at Skarstedt.

Then there were those booths like Luxembourg & Dayan, showing Allen Jones’ female-bodies-dressed-as-sex slaves-presented-as-furniture, which also included Arman’s Don’t Touch (1967) – a mannequin’s body produced from mannequin hands. After viewing these works, it was a relief to enter the Spotlight section. Featuring 24 solo presentations by galleries curated by Adriano Pedrosa, 11 out of the 24 artists showcased this year were women – a pretty good ratio: almost fifty-fifty. And booth upon booth showcased very different twentieth century practices by women artists – some engaging with gender to varying degrees, some not at all.

And so, just over two decades later, if Spotlight is a reflection of changes in the art world, then it was refreshing to see women represented alongside such canonical favourites as Gordon Matta-Clark and Joseph Kosuth, as equals.

But in terms of underscoring why gender should still be an issue today, one work by Judy Chicago presented by Riflemaker said it all. In Chicago’s words (which were written below the print), the work was “…a print made from the center drawing of the Rejection Quintet, five works originally inspired by several experiences I had in Chicago; one with a male dealer, the other with a male collector, both of whom made me feel rejected and diminished as a woman. I decided to deal with my feelings of rejection and in so doing confronted the fact that I was still hiding the real subject matter of my art behind a geometric structure as I was afraid that if I revealed my true self, I would be rejected”. Chicago ends her recollection with an acceptance of her identity, noting: “What a relief to finally say: ‘Here I am, a woman, with a woman’s body and a woman’s point of view.’”

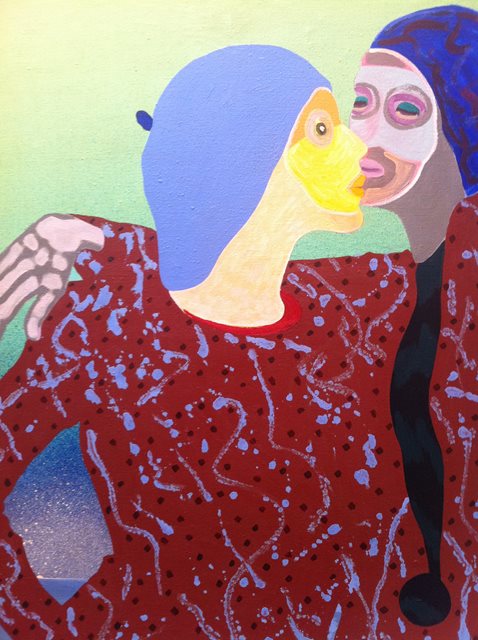

In this, Johann Konig’s presentation of Kiki Kogelnik was inspiring when thinking about the daily struggles women have had and continue to encounter. In Kogelnik’s work, how one might feel diminished by gender while still reacting to such diminishment was vibrantly expressed. Brightly coloured canvases took centre stage with one, It Hurts (1974), depicting a woman prancing across a canvas, with a mask for a face and a pair of scissors positioned by her head – two masks having fallen at her feet. There is an obvious eeriness to the work, tempered by a dynamism in how Kogelnik treats colour and form, most invoked by the use of sheet vinyl and mixed media in another series of works that include a 1970 wall hanging of a skull, which one imagines Alexander McQueen must have seen in his lifetime.

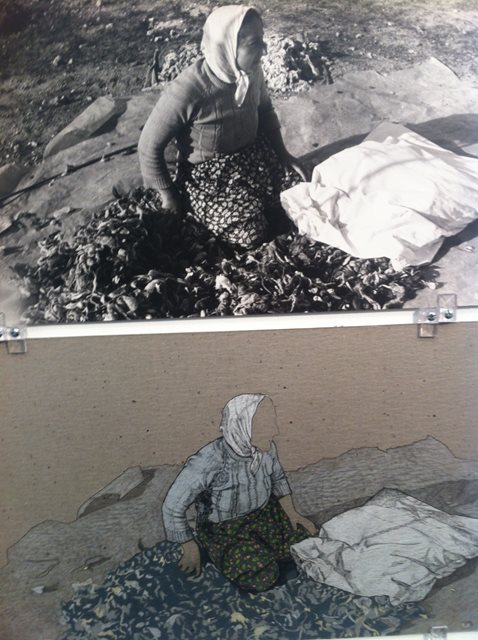

It was illuminating to see Kogelnik’s fraught and forthright pieces next to bodies of work by other female artists at Spotlight, also dealing, in various ways, with ideas of gender. These included documentation from a 1975 feminist dressage performance involving six women dressed as horses staged by performance artist Rose English at Karsten Schubert, and Nil Yalter’s presentation at espaivisor, which showcased an artist practice that, though engaged with women’s issues, extends into the general debates surrounding labour and geopolitics. Works included a project titled Rahime, Kurdish Woman from Turkey (1979) comprising of a video, photographs and drawings that depict the story of Rahime, a Kurdish woman from Turkey, making the transition between her village to a shanty-town in Istanbul.

This connection recalls a phrase: “Where is Ana Mendieta?” that was printed on banners used in a 1992 protest outside the Guggenheim Museum. The protest raised issue not only with the suspicious circumstances of Mendieta’s death (her husband Carl Andre was eventually acquitted in 1988 of her murder), but also the conspicuous absence of women artists from high profile exhibitions at such institutions as the Guggenheim.

Of course, there were others who did not engage directly with gender, such as Liliana Porter at Luciana Brito Galeria, showing images of hands on which shapes are drawn and which extended onto the walls of the booth. Similarly, Irma Blank’s ruminations on writing as a link not to meaning but existence at P420 concentrated more on the idea of breaking boundaries so as to explore how signs might reflect on an unspoken sense of being. And, aside from Lygia Clark at Alison Jacques Gallery, another impressive installation invoking ideas of architecture and space was by Anne Oppermann at Galerie Barabara Thumm, though this was a far more cluttered, sculptural interpretation. Meanwhile, Nancy Spero at Galerie Lelong presented War Series (1966-1970), produced in response to the Vietnam War, not to mention war and oppression in general. Coincidentally, Spero created some of her most memorable works in homage to Ana Mendieta, also represented by Galerie Lelong, and now the subject of a long over-due retrospective currently showing at the Hayward Gallery in London.

This connection recalls a phrase: “Where is Ana Mendieta?” that was printed on banners used in a 1992 protest outside the Guggenheim Museum. The protest raised issue not only with the suspicious circumstances of Mendieta’s death (her husband Carl Andre was eventually acquitted in 1988 of her murder), but also the conspicuous absence of women artists from high profile exhibitions at such institutions as the Guggenheim. And so, just over two decades later, if Spotlight is a reflection of changes in the art world, then it was refreshing to see women represented alongside such canonical favourites as Gordon Matta-Clark and Joseph Kosuth, as equals.

Yet, given the direction that this report has taken, it’s now worth mentioning another work at Frieze London: a poster mounted on hot pink card recalling the Guerrilla Girl aesthetic by Darren Bader presented at Andrew Kreps, which invited women artists to show their work at the First West Coast Open Wall Show for Women Artist’s at the Women’s Building! Of course, this report has done just that – put women into their own category – their own “building” as such, which is the worst thing to do when addressing gender equality, some say.

Nevertheless, I will end not with a response to that point, but with a shout out to Koetser Gallery and their ingenious method of presenting works of historical weight, including one by Jan Brueghel the Elder, with frames constructed from crates hung so that both sides of each work was visible – front and back. Funnily enough, it was this kind of multi-dimensionality that worked at Spotlight, too; like a story being told from both sides, not one. — [O]

via ocula.com