INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

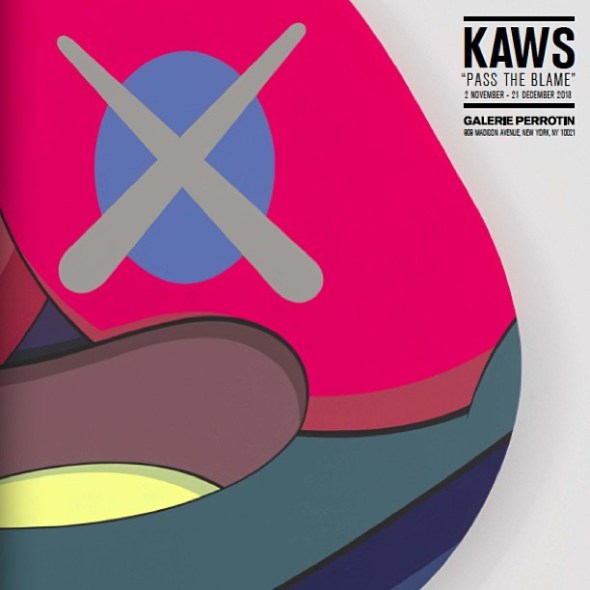

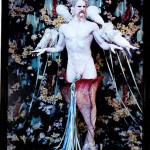

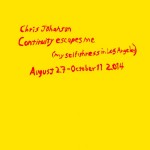

KAWS (A.K.A. Brian Donnelly) occupies a unique position in the contemporary art world. He shows his paintings and sculptures at heavy hitters like Galerie Perrotin yet still designs and sells collectible toys through his company, OriginalFake; this year he also reimagined the MTV Music Awards statuette and contributed the sculptural scenography for the event at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn (the backdrop for Miley Cyrus’s news-hogging twerk-out). This month KAWS has a slew of concurrent exhibitions: “Pass the Blame,” at Galerie Perrotin’s New York location; two enormous sculptures farther downtown at Mary Boone Gallery; a survey at the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas; and a unique outing at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Modern Painters executive editor Scott Indrisek spoke with the artist in his brand-new studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

What will you show at Galerie Perrotin?

I plan to have all shaped canvases, graphic shapes that may or may not recall familiar imagery. To make the paintings, I make drawings and then redraw them on the computer, using Adobe Illustrator, in different layers. Then we print these out, project them, and make color charts. With Illustrator I

can Frankenstein all these images together and experiment with many compositions. For Perrotin, I’m also working on flat sculptures: freestanding and made of high-quality plastics that are typically used for eyeglasses.

For those you’re using a Belgian fabricator. What’s the production process like?

Works like these have never been made. The plastic sheets are outrageously expensive, and you can do all this work, and then get some air bubbles—and you have to toss it and start again.

What about your exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts?

That exhibition will be held in the academy’s Historic Landmark Building, designed by Frank Furness and George W. Hewitt and built in 1876. My paintings will be shown alongside the museum’s permanent collection, so it will be interesting to see them juxtaposed with paintings by Thomas Eakins or Edward Hopper. In one of the galleries, they have a salon-style hanging of smaller works from their collection; for the wall across from it, I decided to mirror the scale and hang of the works with my own, though the content does not reference the earlier works. And I have another project at the museum, the first installment of “The Sculpture Plinth Exhibition Program,” for which I’ll install a sculpture, Born to Bend, above the front doorway of the building. It’s replacing the original marble sculpture on the plinth, which had to be removed because it was deemed unsafe. My sculpture is made of two figures, one being a faceless version of a certain green character that might seem familiar from childhood, and the second being a character that has come to be known as Bendy, who originated when I was painting over advertisements in bus shelters in the ’90s.

With those early street artworks—were you making a critique of the ads themselves?

It was more of a competition for space than a critique of the ads themselves. I grew up doing traditional graffiti, in New Jersey and then New York. In ’93 I started painting over billboards in the same ways I was doing walls, except I started to incorporate the letters I was painting into the images of the billboards. In ’96 I moved to Manhattan, and around this same time I met Barry McGee, who was in town for his show at the Drawing Center. He gave me a tool to open the tamper-proof bolts on phone-booth kiosks, and that’s when I started painting over the smaller ads in those booths. I then figured out how to get into bus-shelter kiosks, and soon after started to do this same type of work in London, Paris, Berlin, Mexico City…

How long would your altered advertisements stay up?

When I was first doing them they would last two or three months before being removed. I would see them every day on my way to work. Later on, though, by the end of 2000 or so, they would only last a few hours. People would break the glass to get into the booth to steal them; it defeated the purpose. Some of them have come back in the secondary market. The first time I visited Takashi Murakami’s studio in Japan, he told me he had a Calvin Klein ad I did with McGee; it had come up for auction at Phillips in 2004. I was surprised because I just assumed it was destroyed, but I guess whoever stole it was savvy. Most of them, I’m sure, just got thrown in the trash.

In 2001 you showed paintings sealed inside packaging, as if they were toys.

I was going to Japan and I had a few friends who would collect everything under the sun—cars, sneakers, vintage clothing, Star Wars prototype figures—but none of them really collected art. Nobody in the younger crowd was buying paintings, so I did this series. It was everything I love about toys and collecting and art and pointing out the parallels between them all. Most people who were collecting toys then didn’t think about art. It wasn’t on their radar, the same way a lot of people who collect paintings weren’t thinking about toys. I guess when I was younger, I always felt there was this hierarchy where art was on a pedestal, and other forms of collecting were thought of as lesser. So I made this series of work where there is no hierarchy. Those package paintings are what got me painting on canvas.

Had you painted in art school?

I’ve painted my whole life. In college I was doing realistic oil painting as well as life painting. At the School of Visual Arts with Steven Assael, who was an incredible life painter, and Marvin Mattelson, who taught me how to paint with a Reilly palette. I would do classical painting all day, and then go out and do really graphic graffiti during the nights and weekends.

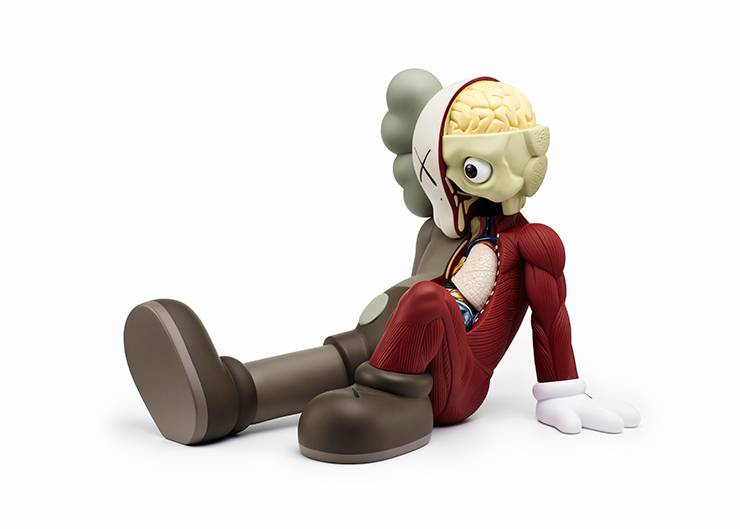

The word toy is so loaded. Have you ever been pushed to rebrand your toys as small editions of sculptures instead?

To me it’s the same thing, except toy implies something to be played with, and my sculptures never had a function other than to be viewed. I always thought it was funny how people like to put things in a category and label them. I have played with this idea a lot. I’ve made bronze pieces, but then painted them in bright solid colors to make them appear like plastic. I’ve also made pieces with a toy factory in China that are four feet tall and have the same presence as any medium-size sculpture. In the end my thought process is the same: I just want to make something good and not worry about how it’s labeled.

via blouinartinfo.com