INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

One of the latest and strangest phenomena of contemporary art – and collecting, fashion and interior design – is the resurgence of interest in the cabinet of curiosities. First created in Renaissance Europe, these collectors’ rooms were microcosms of the universe. Known also as Wunderkammern or Kunstkammern , they comprised astonishingly eclectic assemblages of natural wonders (naturalia), scientific instruments (scientifica), precious art works (artificialia), ethnography (exotica) and inexplicable, miraculous objects (mirabilia) that represented their creators’ interest in understanding and ordering a fast-expanding world.

Most of the great museums of the world grew out of such collections – the unrivalled Kunstkammer of Rudolf II in Prague, for example, is the heart of Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, while the collections of the naturalist John Tradescant – Tradescant’s Ark – formed the foundation of Oxford university’s Ashmolean Museum, and Sir Hans Sloane’s became the nucleus of the British Museum. The rational, scientifically arranged museum, however, rang the death knell for such “cabinets” in the 19th century, as “curio” became a derogatory term and credulous, wide-eyed wonder was relegated to the freak show.

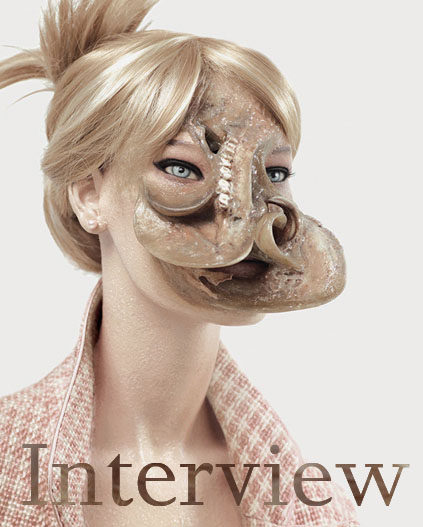

So when did wonder abandon the fairground for the art fair? Certainly, in contemporary art the natural world is everywhere – pinned, pickled, stuffed, stripped to the bone and, often, alarmingly hybrid – and the tentacles of this faunamania extend far into fashion and design. In that emporium of sartorial avant-garde, Dover Street Market in London, for example, the first thing you see is a glass cabinet of antlers, the skull of a crocodile, stingray vertebrae and an exploded crayfish, as well as jewellery ornamented with scarabs, skulls and tiny seahorses.

It was probably the surrealists who rekindled the peculiar flame of the Wunderkammer. André Breton’s famous “Wall”, begun in the 1920s and now in the Centre Georges Pompidou, was an apparently random selection and disposition of natural wonders, “found” objects, and tribal and western art whose value lay in its juxtaposition. The boxes produced by the surrealist-inspired Joseph Cornell evoked not only the contents but the physical appearance of the compartmentalised collectors’ cabinets produced in Augsburg and Antwerp in the 17th century.

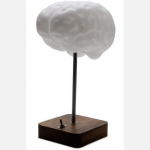

Then came the YBAs, and Damien Hirst in particular. It is hard to imagine that Hirst had never seen the earliest pictorial records of natural history cabinets – those of Ferrante Imperato (engraved in 1599) with an enormous crocodile suspended from its ceiling and Ole Worm, where walls and ceilings are lined with preserved fish, stuffed mammals, turtle shells, corals, specimen jars and their ilk. It was Hirst’s genius to reinvent such contents on a sensational scale – specimens in formaldehyde, butterfly paintings, medicine cabinets, skulls …

In titling his works – the 14ft-long tiger shark is “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” – he places them firmly in the melancholic vein of those early collectors so often also obsessed with mortality. Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull is another memento mori alluding, like all Vanitas symbols, to the ultimate meaninglessness of earthly goods and pursuits.

While there have always been collectors of the virtuoso, precious objects once included in cabinets of curiosities – lavishly mounted rock crystals or ostrich eggs, intricately carved ivories, small-scale statues or jewel-like paintings, antiquities and Chinese porcelains – the 20th century also saw a return to their artful assemblage and presentation. A lineage of dealers running from Nicolas Landau and Kugel to Axel Vervoordt, Georg Laue and Finch & Co has effectively reinterpreted these cabinets for a contemporary audience.

A good example of contemporary display is the 600-piece collection of Jacques and Galila Hollander, which is expected to fetch €4m-€6m at Christie’s Paris on October 16. It took half a century to amass this extraordinary theatrum mundi but what is particularly striking is the way in which the Hollanders presented it in their Brussels home – in a wall-size grid of individual vitrines illuminated by a computerised lighting system.

Kunstkammer and contemporary art have also come together in the collections of Thomas Olbricht, displayed in the Me Collectors Room in Berlin. Georg Laue was responsible for this installation, and the Munich dealer now collaborates with London Old Master dealer Colnaghi to stage what promises to be one of the most imaginative shows of Frieze Week. Art of the Curious: an Exhibition of the Rare, the Bizarre and the Beautiful (until October 25) juxtaposes Kunstkammer objects, cabinet pictures and drawings with the work of a carefully selected group of contemporary artists commissioned by Colnaghi’s Katrin Bellinger.

A good example of contemporary display is the 600-piece collection of Jacques and Galila Hollander, which is expected to fetch €4m-€6m at Christie’s Paris on October 16. It took half a century to amass this extraordinary theatrum mundi but what is particularly striking is the way in which the Hollanders presented it in their Brussels home – in a wall-size grid of individual vitrines illuminated by a computerised lighting system.

Kunstkammer and contemporary art have also come together in the collections of Thomas Olbricht, displayed in the Me Collectors Room in Berlin. Georg Laue was responsible for this installation, and the Munich dealer now collaborates with London Old Master dealer Colnaghi to stage what promises to be one of the most imaginative shows of Frieze Week. Art of the Curious: an Exhibition of the Rare, the Bizarre and the Beautiful (until October 25) juxtaposes Kunstkammer objects, cabinet pictures and drawings with the work of a carefully selected group of contemporary artists commissioned by Colnaghi’s Katrin Bellinger.

Long believed to be the horn of the elusive unicorn, these tusks were arguably the greatest treasures of any cabinet of curiosities – Pope Clement VII acquired one for more than five times the amount he paid Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Equally in demand was the bezoar – an intestinal mass – that was believed to be an antidote to poison. It is these kinds of mirabilia, along with the likes of mutant two-headed sheep that, one suspects, particularly appeal to certain contemporary artists. A flick through the “Thinking Big” catalogue of sculpture and installation being deaccessioned from the Saatchi Gallery and sold at Christie’s on October 17, for instance, reveals cow stomach (Peter Buggenhout), fantastical multiheaded skeletons (Shen Shaomin), conjoined children (Jake and Dinos Chapman) and a repellent transmuted human form dripping out of a vitrine (Berlinde de Bruyckere).

Frieze Week will furnish many more examples, old and new. At Frieze Masters, for instance, Daniel Katz will show a 19th-century north Italian marble head of a beautiful young woman in profile that, once turned, reveals her face decomposing to expose the skull beneath (£125,000). He could have sold the 17th-century marble skull resting on an aged book displayed on his stand last year several times over. The Other Art Fair (October 17-20) offers taxidermy classes and demonstrations.

Beyond London, at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Howarth (until December 31), the surrealist photographer Charlotte Cory’s “Visitorians” continue to offer their alternative post-Darwinian narratives. In the artist’s enlarged-scale collages and montages of tiny Victorian cartes-de-visite, the heads of the long-anonymous sitters are replaced by those of – photographed – taxidermied animals.

By Susan Moore

via http://www.ft.com