INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

Identity remixed in provocative displays at the Jewish Museum, the New Museum, the Whitney, and Tate Modern as follows:

In 1994, Elaine Reichek, an artist from Flatbush, Brooklyn, installed a version of her childhood bedroom in the Jewish Museum.

Installation view of “Elaine Reichek: A Postcolonial Kinderhood Revisted,” opening tomorrow at the Jewish Museum in New York.

PHOTO: CHRISTINE MCMONAGLE/THE JEWISH MUSEUM. COURTESY THE JEWISH MUSEUM, NEW YORK.

She set up a four-poster bed from the Ethan Allen 1776 collection, just like the early American furniture her parents bought for her. She painted the walls a sinister shade of green. She brought in a washstand, braided rugs, a fire screen, samplers, and other decorative touches suitable to the typical New England colonial-era home.

In other words, the bedroom in A Postcolonial Kinderhood didn’t look Jewish at all. It wasn’t supposed to. It was home décor as assimilation tactic, a way for new arrivals to insert themselves into the narrative of American history. “Wanting ‘to pass’ was an issue in my childhood,” the artist says. “My parents wished they grew up with those samplers.”

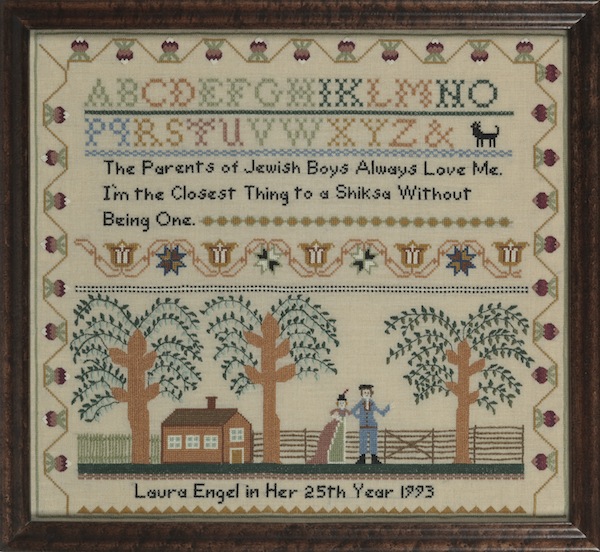

Well, maybe not these particular samplers, which are embroidered with comments from Reichek’s friends and family about their Jewishness. “The parents of Jewish boys love me,” reads one. “I am the closest thing to a shiksa without being one.” (A shiksa is a pejorative word for a non-Jewish woman; the speaker was the artist’s daughter.)

Elaine Reichek, Sampler (Laura Engel), from A Postcolonial Kinderhood, 1993, embroidery on linen.

COURTESY THE JEWISH MUSEUM, NEW YORK.

To an audience accustomed to earnest reconstructions of the lost worlds of the shtetl and the Lower East Side, Reichek’s sinister rendering of the next stop on the Jewish American journey was audacious. Where was the nostalgia?

The reaction, positive and negative, is among the documentation that will be added to the piece when it reappears in the galleries tomorrow, 20 years after it was commissioned.

This is the third time the Jewish Museum has shown A Postcolonial Kinderhood, which it acquired in 1997.

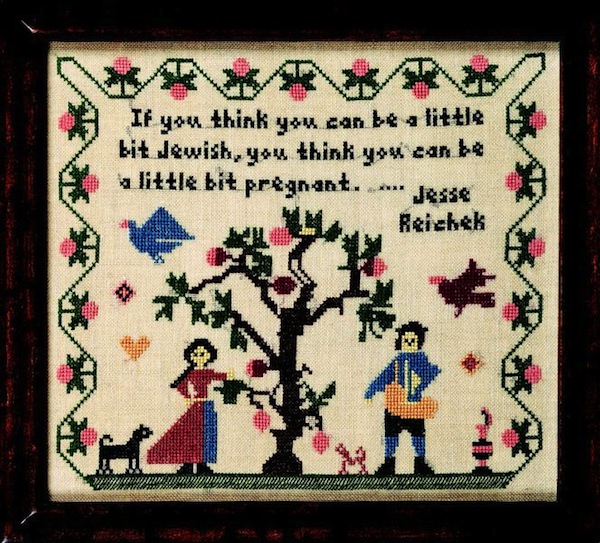

Elaine Reichek, Sampler (Jesse Reichek), from A Postcolonial Kinderhood, 1993, embroidery on linen.

COURTESY THE JEWISH MUSEUM, NEW YORK.

The second time was in 1996, when curator Norman Kleeblatt included part of it in “Too Jewish?”, his survey of how Jewish artists were challenging traditional identities. “This was one of the handful of works that jumpstarted the discussion of Jewish identity within the larger framework of identity politics and multiculturalism,” says Kleeblatt, the museum’s chief curator. “Jews worked so hard to assimilate, and were so successful at it, that they weren’t even considered a marginalized group in the multicultural discussions. Yet growing up, the baby-boomer generation (and the one before) still experienced subtle anti-Semitism and sensed themselves as being outsiders. But unless it was a woman, gay or lesbian, Jewish didn’t count.”

With newly added personal memorabilia, “Elaine Reichek: A Postcolonial Kinderhood Revisited” introduces the artist as an actual character in the piece, who left Brooklyn and studied at Yale before embarking on her sometimes controversial art-world career. Which is real and which is fiction? Will the s-word still raise eyebrows? How does this reflect on the immigrant experience a generation after it was made?

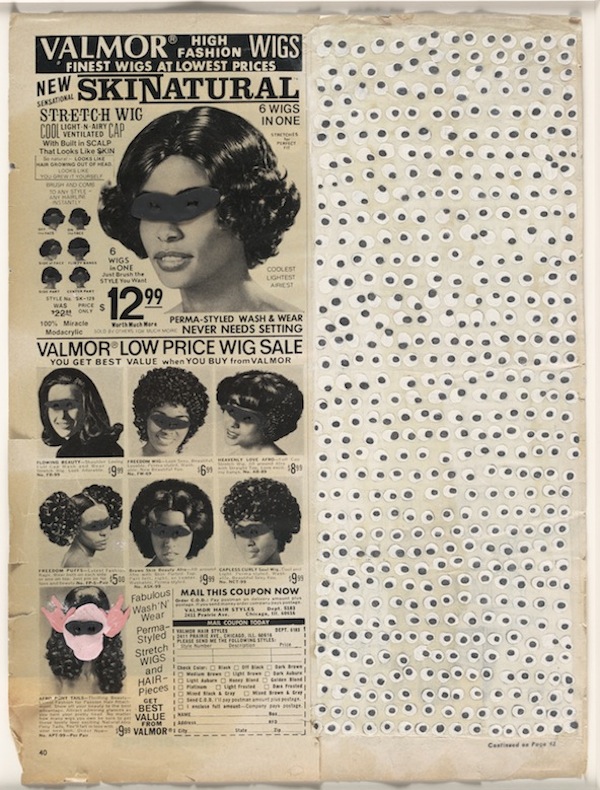

Ellen Gallagher, Skinatural,1997, oil, pencil and plasticine on magazine page.

COLLECTION MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. GIFT OF MR. AND MRS. JAMES R. HEDGES IV.

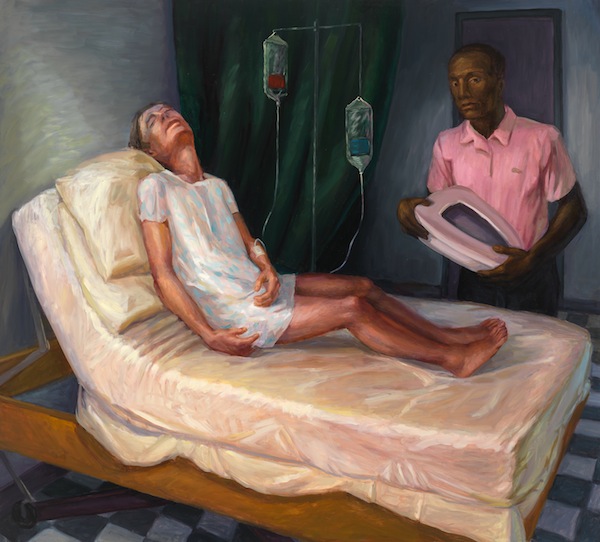

Hugh Steers,

Bed Pan, 1994,

oil on canvas.

COLLECTION OF WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART. GIFT OF WHEELOCK WHITNEY III IN MEMORY OF THE ARTIST.

-via artnews.com

Copyright , ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th St 9th FL NY NY 10018. All rights reserved.