INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

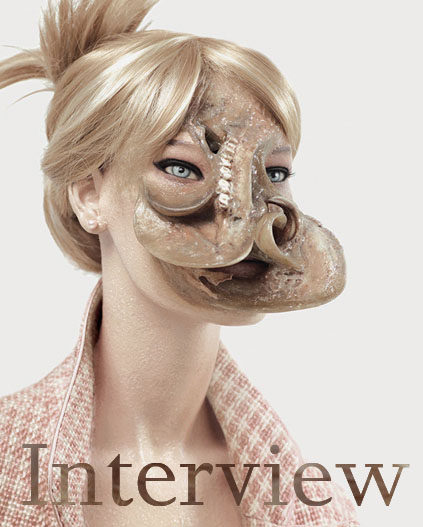

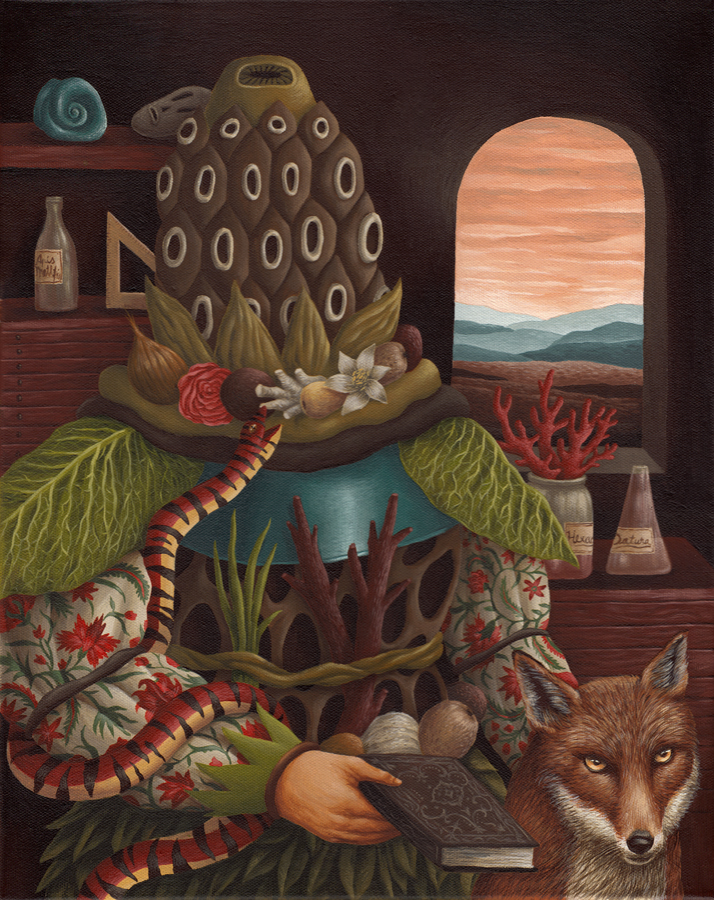

Influenced by artists like P.P.Pasolini, Werner Herzog, Elfriede Jelinek, Hieronymus Bosch or Diane Arbus, the 61-year-old Austrian director Ulrich Seidl questions in his films notions like normality, beauty, reality, giving visibility and power to prototypes often marginalized, to outsiders (the ugly, the fat, the poor) and presenting everyday situations in a grotesque-realist cinematic style.

After years in documentary filmmaking (a powerful example is Animal Love, a documentary about the strong relationships between people and their pets), the director has turned to fiction, making films like Dog Days (2001) and Import ̸ Export (2007). Even if he says that he is not interested in portraying reality and that his work is “very artificial, strongly dependent on carefully constructed imagery”, the mixture of documentary and fiction techniques is widely used in his filmography. He blends authentic details with staged ones, professional actors with amateurs, a structured dialogue with an improvised one.

The three films of Paradise Trilogy: Paradise: Love (2012), Paradise: Faith (2012) and Paradise: Hope (2013) are released separately so they can be watched separately. This boschian triptych continues his previous work, focusing on desperate lonely contemporary women. Satirically titled Paradise Trilogy, the films show with a cruelty à la Haneke the ruinous ways in which the characters are struggling and failing to conquer the Happiness, through Christian values like love, faith and hope.

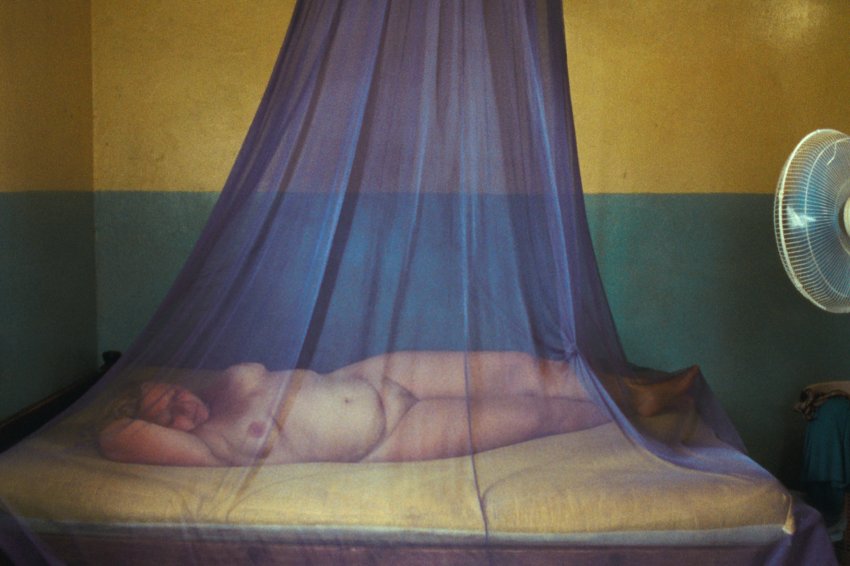

In the first part, Teresa (Margarethe Tiesel), an obese 50-year-old lonely woman, leaves her teenage obese daughter Melanie (the central character of later Paradise: Hope) in the care of her sister and goes for a solitary vacation in Kenya. This exotic destination is the pretext for Seidl to explore themes like sexual tourism, colonial relations, exploitation and women’s liberation. Following the advice of a friend she meets there, Teresa starts to hook up african beach boys (taxi drivers, vendors) just to satisfy her lack of love and her sexual desires, in exchange of money. But soon we figure out that the exploitation is mutual (while the white women treat the local boys as commodities, the kenyans, on their turn, take advantage of the money of the European women), and that the pursuit of love is futile and tormenting.

The second part portrays the intimate life of a middle-aged fanatic woman: Anna-Maria (Maria Hofstätter), the sister of Teresa from Paradise:Love is a medical technician, who devotes her free time to missionary work and religious rituals. More precisely, she walks on the streets of Vienna, from door to door, carrying a statue of the Virgin Mary to bring people (mostly immigrants) to the right path, to Christianity. At home, she flagellates herself or plays religious songs on her electronic keyboard. Everything changes when her disabled Muslim husband appears home, unexpectedly, after two years of absence. Anna-Maria turns to be not so compassionate with her husband as Jesus would demand, treating him in an offensive way.

She completely ignores him, she forbids things to him, she refuses to have sex. Instead, she gives in all her love to Jesus, sublimating her erotic desire (in a provocative scene, because of which Seidl was accused of blasphemy, Anna-Maria is masturbating herself with a huge crucifix). The husband replies in an aggressive way, so the conflict between them is getting worse, occasion for Seidl to refer to the aggravation of the war between Christianity and Islam.

We said that the work of Seidl has the air of a grotesque realism, in a bakhtinian sense. He is interested in the human body as it is dominated by the primare needs, in the human body treated as an object. He uses exaggerated, grandiose grotesque images and grotesque situations (sexual orgies, sadomasochism, profanation) to explore degradation and depravation. Despite the fact that he is oftenly accused of cynism, misanthropism or pessimism, Ulrich Seidl manages to keep a humanist regard toward his characters generally put in embarrassing situations and to induct a form of empathy for the viewers.

by Andreea Andrei

Andreea Andrei studied Performing Arts (Arts du Spectacle) at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. For the moment she is an independent researcher, interested in the critical potential of art and in the artistic power of criticism.