INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

“Contemporary art is a relatively cheap way of criticizing the system,” wrote Russian artist and curator Arseniy Zhilayev in “The Lessons of the Biennale Season.” In one of several critical essays on the state of the Russian art world in the 2013 volume “Post-Post-Soviet,” Zhilayev focuses his ire on the role of contemporary art in the machinations of a semi-authoritarian regime. “The authorities need a liberal façade to put up the appearance of democratic transformations, “ he explained, discussing 2009’s third Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art. By permitting small-scale political gestures within the art world, the Russian government could point to contemporary art as supposed evidence of its tolerance toward cultural and dissident activities.

Zhilayev’s concerns were sidelined when the Manifesta Biennial announced that it would hold its 10th edition in St. Petersburg, Russia, under the direction of curator Kasper Konig. Many Western commentators, evidently unfamiliar with contemporary art politics in Russia beyond the much-publicized incarceration of Pussy Riot, argued instead that art should criticize the system. Shouldn’t international curators and artists refuse to work in Russia, many asked, as acts of opposition to the state’s repressive LGBTQ laws and maneuvers in Ukraine? Wouldn’t it simply be better to hold the biennial elsewhere? Manifesta 10, which opened on June 28 at the State Hermitage Museum, proves that disengagement from Russia would have been a cop-out, akin to turning a blind eye while the country’s government spirals further into conservatism and militarism. The exhibition is a mixed bag — many such large-scale shows often are. But when artworks in Manifesta 10 do achieve critical ends, they succeed not by explicitly attacking contemporary Russian politics, but by illustrating through more suggestive mechanisms the disturbing state of political affairs and policies in the country.

Inside the General Staff building, newly restored on the occasion of the Hermitage’s 250th anniversary, Manifesta 10 presents the largest exhibition to date of international contemporary art in Russia. Across all four floors, special commissions by many leading Western names and pieces from a select few Russian artists purport, as per Manifesta’s manifesto, to interrogate the shifting boundaries of East and West in Europe.

Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Abschlag” installation, which occupies the first room on the main floor, offers a lesson in how not to engage with the Russian milieu: the Swiss artist constructed part of a typical Petersburg apartment block out of cardboard inside the full-height space, ripped off its façade, and deposited the refuse at its base, revealing shabby interiors lined with original avant-garde masterpieces (on loan from the nearby Russian Museum) by the likes of Malevich and El Lissitky. The references allude to a politically radical Russian past; the construction debris acts as a metaphor for history. Though Hirschhorn suggests a recovery of the revolutionary communist spirit of the 1920s, he falls prey to a historically revisionist fetish: citing the Russian avant-garde as a generative point for vanguard culture in the West, and offering it as a source for renewed progressivism in Russia. Hirschhorn seems woefully unaware of the Putin government’s branding campaign, one that aims to sell the Russian avant-guard as a nationalist movement in line with the regime’s own values (perhaps he didn’t watch the Sochi opening ceremony). Hirschhorn ultimately proves Zhilayev right — with its political pretenses, “Abschlag” aspires to make a grand gesture against conservatism, but fails because its critique has already been co-opted.

Dmitry Prigov’s “Installation with names of artists,” one floor up, offers an alternative treatment of the avant-garde legacy: blank canvases hang on three walls, accompanied by signs that announce in English, “There is Malevich,” “There is Rembrandt,” “There is Matisse.” The pieces in question are actually elsewhere — Malevich’s “Black Square” hangs on the opposite wall while Matisse hangs on the third floor and Rembrandt inside the Winter Palace — but the painters’ names and reputations, Prigov jokes, matter more than their art. Prigov, unlike Hirschhorn, knows that Malevich inspires stronger feelings in Russia’s elite art collectors than in its 21st-century would-be revolutionaries.

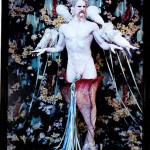

Prigov is but one of a small handful of Russian artists included in Manifesta 10. Though headline-grabbing names include the Kabakovs (who are long boring) and Pavel Filonov (who is long dead), the lesser-known Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe cuts the most impressive figure among the biennial’s artists, Russian and otherwise. A cross-dressing Marilyn Monroe impersonator, the photographer, performer, and video artist emerged in the midst of late 1980s perestroika chaos and became an icon of the St. Petersburg underground scene. Mamyshev-Monroe continued to play with the persona until his death last year under uncertain circumstances; many believe he was murdered.

His 1993 “Tragic Love” series of black-and-white photographs feature the artist dressed as Monroe, parting with a youthful paramour. Teardrops drawn by the artist onto the photograph and a dash of red pencil on her hat heighten Mamyshev-Monroe’s sardonic attitude toward the taboos of cross-dressing and gender bending. Despite its political imagery and implications, Mamyshev-Monroe’s work was never explicitly political; he dressed as Marilyn because of the deep personal appeal the actress held for him, not because he aspired to comment on the role of homosexuals in Russia by appropriating her as a gay icon. He stands against a backdrop showing the Kremlin wall, blowing air kisses in full-on Marilyn makeup in the 2005 photograph “Monroe,” from his StarZ series — playing with absurdist humor to reference homosexuality in Russia. His inclusion at Manifesta elevates Mamyshev-Monroe beyond the local underground, exposing a large and largely Russian audience to his work while bringing him into the narrative of international contemporary art history. His work eschews explicit references to homosexuality, making it acceptable — though just barely — in a setting as official as the Hermitage. An older tour guide leading students through Mamyshev-Monroe’s rooms curtly announced, “Moving on.” Yet some of the youth lingered, obviously intrigued.

Marlene Dumas’s watercolor paintings of famous gay men hang across the square inside the Winter Palace, where the Hermitage’s vast collection is on permanent display. The portrait series was commissioned specifically for Manifesta 10, and meant to address LGBTQ rights in Russia. Originally titled “Famous Gay Men,” the series appears in a third-floor gallery flanked by post-impressionist rooms on either side, with “gay” now removed from its moniker. The series retains its 16-and-up designation, however, advising parents to steer their brood clear of James Baldwin, Tchaikovsky, and their cohort. What, the visitor wonders, makes these steely images of “Great Men” inappropriate for children? Absolutely nothing.

Manifesta succeeds in these particular moments when it reflects the cultural and political conditions under which it operates. “Are things so bad that Manifesta 10 might be considered a positive, ‘civilisational’ event no matter what its content, by sheer dint of taking place in a country plummeting into the abyss of militarist aggression, obscurantism, and proto-fascist nationalism?” critic and curator Ekaterina Degot asked in a recent essay. Throughout the Hermitage halls, the answer appears to be yes. Open, public discussions of sexuality, gender norms, Ukraine — and other hot-button issues like migrant worker abuses — appear largely unacceptable in today’s Russia. In broaching, if not comprehensively addressing, these issues, Manifesta 10 speaks to two audiences. For many international visitors, the lack of openly critical works might be the richest critical position in the show; for local viewers, suggestive works like Mamyshev-Monroe’s might inspire reflection. Yet the most telling measure of this biennial’s success will come in its aftermath. Contemporary art can’t change the political system in the country, but perhaps it can give citizens a clearer picture of their surroundings. And while that’s only a start, it’s much better than nothing.

via blouinartinfo.com