INHALE is a cultural platform where artists are presented, where great projects are given credit and readers find inspiration. Think about Inhale as if it were a map: we can help you discover which are the must-see events all over the world, what is happening now in the artistic and cultural world as well as guide you through the latest designers’ products. Inhale interconnects domains that you are interested in, so that you will know all the events, places, galleries, studios that are a must-see. We have a 360 degree overview on art and culture and a passion to share.

Bringing together a body of entirely new work across two floors of the gallery, Making Eden explores the theme of revolution, drawing a stark contrast between the utopian ideals inherent in anarchic action and the darker realities of its consequences. Particularly pertinent in today’s global climate of social and political disillusionment, Shonibare explores both historical and contemporary cycles of revolution, seeking to demonstrate the destructive patterns of human behaviour that repeat themselves across time.

Making Eden interprets literally the notion of overthrowing the current social order in favour of an imagined ‘better place’. The exhibition functions in two halves: the ground floor mirrors this perceived utopian realm – a paradise that is reminiscent of heaven itself, while the upper floor is a representation of the grotesque reality of the corrupt and the fallen, as if the viewer is walking into hell. Indeed, Shonibare once described how ‘enlightened intentions, in sum, do not necessarily produce enlightened results’. This view is reflected in the horrific reality of the violence and death depicted, which has occurred as a direct result of revolution.

Ms Utopia (2013) stands in the downstairs gallery, a tall female figure clutching a towering bunch of African batik fabric flowers. Operating as a symbol of peace, she appears as the figurehead of this newly established ‘Eden’. However, the aesthetic allure of both the flowers and the fabric itself, as in much of Shonibare’s oeuvre, serves as a contradictory façade to the truths that are explored here. The batik fabric – which signifies authentic African heritage while being manufactured in the Netherlands and then distributed in the UK – continues Shonibare’s characteristic practice of using materials that allude to artifice and ambiguity, and to the unsettling fragmentation and hybrid construction of identity.

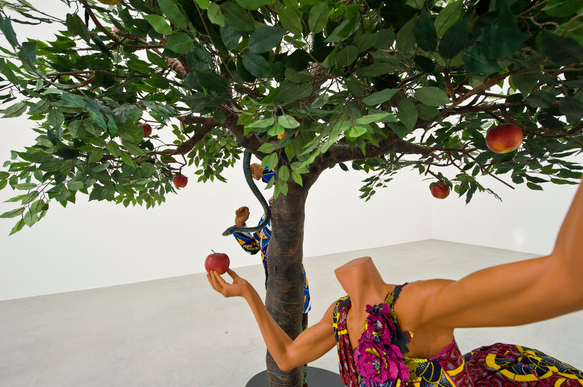

Also present in this section of the exhibition are Adam and Eve (2013) and Eden Painting (2013). The former is a sculpture of the two biblical characters resting beneath a tree, giving the viewer the unmistakable impression that they have stepped into a constructed paradise. The latter work is a large-scale wall piece which comprises a range of animals and images from the story of Noah’s Ark to create an otherworldly constellation that evokes idealistic sensations of unity, balance and harmony.

On the upper level, we encounter an opposing realm of chaos and bloodshed, in which works such as Revolution Ballerina (2013) and Impaled Aristocrat (2013) are situated. The latter is a male figure suspended in motion as he falls to his death; the aristocrat’s body has been pierced by a sword, providing a visual allegory of the potential backfiring or downfall of revolutionary processes.

Perched on a tightrope on the second floor of the gallery is Revolution Kid (Calf) (2013). The figure is an overbearing presence indicative of the act of protest, and suggests a tense balancing act that could in theory come plummeting down into the peaceful realm of ‘Eden’ below. Holding a golden gun in one hand and a blackberry phone in the other, the work possesses a number of subtle references; the handgun is modelled on that of Colonel Gaddafi’s at his moment of capture in 2011, while the blackberry phone alludes to the London riots of the same year, which were largely coordinated by teenagers via smartphones and social media. The figure, whose head has morphed into that of a calf’s, pays homage to the figure behind Liberty in Eugene Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) – perhaps the most celebrated work on the theme of revolution in the history of art.

Making Eden ultimately serves to capture the double-edged, ambiguous nature of revolution, which is reflected by the exhibition’s polarised representations of its effects. For while perpetual cycles of uprising and demise can produce damaging results, they also function as necessary demonstrations of hope, and of the human propensity toward change for the better. Indeed, Shonibare acknowledges how, ‘In the short term, on an individual level, you have to work to get yourself to a better position; even if it’s some kind of utopia, you make an effort, you don’t sit back and allow yourself to be oppressed, you fight. I think that’s important. People have to judge history later on’.

via blainsouthern.com